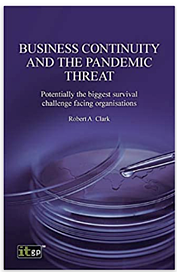

Business continuity expert and author of the book Business Continuity and the Pandemic Threat, Bob Clark, joins Danielle Ricci, Vice President of Marketing for AlertFind, to talk about how companies can improve their business continuity programs and the core elements every organization needs to have.

Danielle Ricci: What principles do business continuity managers need to understand before starting the process?

It’s really a case of getting organizations to learn how to walk, then run, when they’re new to business continuity. Or if they’ve got some understanding of business continuity, then try and keep it as simple as possible. And this is one way of doing it.

Look at things from a scenario perspective rather than a plan for every possible eventuality. You can’t do that. I’ve never come across an organization - including the likes of IBM and other major corporations — that have covered every option. It’s just not possible.

Danielle Ricci: How do you, as a business continuity professional, start to shift from a very specific threat perspective to a scenario- or process-driven approach?

Bob Clark: If you think about threat analysis, you’ve usually got production process disruption on the one hand, and on the other, you’ve got a number of issues, human resource issues, plant equipment, single points of failure, security exposure, etc.

The question you should be asking is, “Is it short-term, medium-term or long-term?” And you should have a different response depending on what the answer to that question is.

Your risk assessment is likely to show some of those threats are more likely to happen to your organization. If you look at human resource issues, you’ve got all those things that could affect it. It could be a fire that injures employees, terrorism, a pandemic, etc.

All these things have a common denominator in that they’re affecting your human resources and your organization’s ability to produce goods or services.

So by addressing it and saying, “So what are we going to do if the power goes off? What are we going to do if there’s some malicious damage? What are we going to do if there’s a cyber attack?”

Then you find that your plan is simplified because you’re not trying to come up with plan A, plan B, plan C, plan D, plan E to reflect every possible risk.

Danielle Ricci: So what are the core elements of a business continuity plan that businesses need to put in place to support this scenario-based approach?

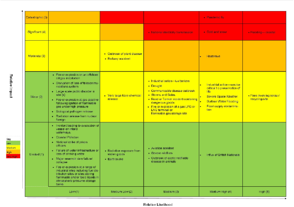

Bob Clark: First, you need to undertake a risk assessment. There may be scores of threats that you’re considering. But you need to work out your red ones, which are the ones that are considered hot items, and then the amber ones, which need attention but aren’t top priority.

Some organizations already have risk management embedded. If so, use what you have. But ideally, you should have a risk register.

After all the risks are recorded, then you need to ask, “What are we going to do about this risk? Are we going to sit there and look at it?”

Then you want to map your risks into a 5 by 5 matrix, like this one in the U.K. Risk Register.

The most severe and most likely risks go in the upper right corner. The less severe and less likely risks are in the lower left corner.

Danielle Ricci: So how do you put this scenario-based approach into action?

Bob Clark: For example, say there’s a fire. Your first priority is get people out of the building. This is where we have a crossover with emergency preparedness. Business continuity isn’t looking to reinvent the wheel or come up with a better way of evacuating a building. What it’s looking to do is to hook into what is there.

If you find that “Oops, we don’t have an emergency preparedness plan for a building evacuation,” then clearly one needs to be defined. Getting people out of the building is your first priority. Then you start looking at the questions in terms of the short-term, medium-term, long-term plan. If the building is destroyed and you’re not going to be back in there for a long time, then clearly, you need a long-term contingency plan. Do you have another building that you can use? Do you have an arrangement with an office space rental company like Regis?

On the other hand, if it’s just a short-term issue where you need to be out of the building for 24 hours, then everyone goes home and comes back in tomorrow as normal. This is how you would need to react.

You also need to determine who owns the particular plan for each specific area. Now, the person that owns the denial of access plan might be the person responsible for the buildings. The person that owns the human resource issues may be the human resource or the personnel department. The person that owns the IT failure could be the IT manager or the CIO. It’s not necessarily going to be the same person responsible for every plan.

Danielle Ricci: Most companies have one person or a small team in charge of business continuity. What other people and departments should they pull into the process?

Bob Clark: Clearly there needs to be a reporting line. You will have an incident or crisis management team set up which, depending on how big or small the organization is, will handle the incidents. You would need obviously regular updates on the status of the incident resolution. You let the people that are best positioned and have the appropriate experience and the skillset sort out whatever the problem is. And sometimes that could mean bringing in external expertise. Sometimes you can deal with it in-house. It depends entirely on what the issue is.

You need someone to be leading it from the business continuity perspective, and that individual needs to be empowered by someone who is sitting on the board. If there’s no upper-level support, then I’m afraid you’re wasting your time. Because if the board does not have visibility, or if the board is not interested in it, then it doesn’t matter how dedicated people are at a lower level; it’s not going to happen.

You need someone to be leading it from the business continuity perspective, and that individual needs to be empowered by someone who is sitting on the board. If there’s no upper-level support, then I’m afraid you’re wasting your time. Because if the board does not have visibility, or if the board is not interested in it, then it doesn’t matter how dedicated people are at a lower level; it’s not going to happen.

You’re also going to need IT to be involved. They may produce their own plan for how to recover from a disaster which affects IT, but they still need to be working to the same parameters that the business is.

Danielle Ricci: So what’s the next element in your business continuity process?

Bob Clark: Next you need to look at your business impact analysis. This tells you which of your processes, which of your services, which of your products are at risk from the various threats that you’ve analyzed.

It’s part of the overall process of analysis, which is your business impact analysis and your risk assessment combined, so that you can say, “Well, these are the things that are important to us. And these are how quickly we need to recover them in the event of an interruption to the business. And these are the risks that really caught our attention that we need to be looking at and see if we can do something about it from the mitigational contingency perspective.”

It’s the combination of those two things which puts you in a better position to make business decisions. So if someone says to you, “Why did you do that?” you’ve got the supporting rationale for your choice. The business impact analysis and the risk assessment are key to that.

Danielle Ricci: What role does governance play in the process?

Bob Clark: Business continuity needs to become part of the culture. There’s no point in having the world’s best business continuity plan if no one knows what’s in it and what their part in the whole process is. That is really about your governance from the management point of view, from the policy point of view, from the awareness point of view, which takes us to what would be referred to as the technical professional practices within business continuity.

First you have the analysis, made up of the business impact analysis and risk assessment. Second, you look at your strategies. What are you going to do? Third, is writing your business continuity plan, which defines how you’re going to do it. Then the final stage is validation, which can include exercises, drills, discussions, etc.

You have to make sure you have the foundational pieces correct or the whole plan is useless.